See No Evil

Simone Leigh at the Venice Biennale

The Venice Biennale is a show with two parts. One is a curated international exhibition. The other is pavilions, each owned by a different country, each of which chooses an artists to represent it in that pavilion. The international exhibition of the 59th Biennale was curated by Cecilia Alemani, an Italian woman who for over a decade has been the director and chief curator of New York City’s High Line Art Program.

When Alemani was named Curator and Artistic Director of the 59th Venice Biennale in 2022, she said, “as the first Italian woman to hold this position, I understand and appreciate the responsibility and also the opportunity offered to me….I intend to give voice to artists to create unique projects that reflect their visions and our society.” Since the beginning of biennales, in 1895, there have been more male artists than female artists invited to participate. But this year, Alemani decided that the status quo wasn’t the way to go. Of the 213 artists in this Biennale, only about 10% were male. Which is the exact opposite of the 1995 Biennale, a ‘normal’ biennale at which 90% of the artists were male. Even at biennales curated by women, the invited artists have been mostly men. As Maura Reilly noted in ARTnews, “the only such large institutional group shows anywhere that have a larger proportion of women artists than Alemani’s are…museum shows…devoted to female artists.”

Georgia O’Keefe refused to participate in Peggy Guggenheim’s groundbreaking exhibition of women artists in 1943. Because she said, she was an artist, not a woman artist. How should a woman respond to an invitation to participate in an exhibition when the field is stacked in her favor. Well, the field has always been stacked in white men’s favor (until I had a son, that is) and none of them seems to have objected. Maybe some of the artists selected by Alemani made the cut because they were women, or women of color, or people whose political agendas or sexual orientation seemed right for this moment in time. But Simone Leigh wasn’t one of them.

Simone Leigh’s work was everywhere. In Alemani’s curated Arsenale show, in the United States Pavilion, as the first black woman artist chosen to represent the United States and at other venues throughout Venice.

I immediately responded to Leigh’s work on a visceral level, but I suspected there was more, so I set out to learn more. And the more I learn, the more I appreciate the idiosyncratic and intelligent ways Leigh draws upon her sources, subtly subverting some, courageously celebrating others. Leigh’s work is both aesthetic and political.

Simone Leigh (Figure 1) was born in 1967 to Jamaican missionaries who had emigrated to Chicago. The neighborhood was a segregated one, says Leigh, "Everyone was black, so I grew up feeling like my blackness didn’t predetermine anything about me. It was very good for my self-esteem. I still feel lucky that I grew up in that crucible.”

Figure 1. Simone Leigh at US Pavilion, 59th Venice Biennale, 2022

Leigh attended Earlham College, a Quaker school, where she received a solid education in the humanities. How else could she say, ”I came to my artistic practice via the study of philosophy, cultural studies and … African and African American art…” Leigh is a feminist whose work celebrates marginalized women of color by making their experiences central to her work, what she calls, “black female subjectivity”.

Visitors to the Arsenale were greeted by Leigh’s 16 foot tall bronze statue of a black woman called Brick House. (Figure 2) Cecelia Alemali had commissioned Leigh to create this piece in 2019 for the newest section of the High Line, the Plynth, where 30the Street meets 10th Avenue. (Figure 3) For 2 years, the statue silently kept watch high above the crowded streets of New York City. It is the first of a series by Leigh that combines the human body with architectural forms from Africa and the American South.

Figure 2. Brick House, Simone Leigh, Arsenale, 59th Venice Biennale, 2022

Figure 3. Brick House, Simone Leigh, High Line @ 10th, New York City

The statue’s hair is plaited with cornrow braids that fall to either side of her head. At the end of each are cowrie shells. (Figures 4, 4a) Cowrie shells are everywhere in Leigh’s work and they have a long history in Africa. They were crafted into jewelry and fashioned into hair ornaments; they were used in religious rituals and as protective amulets. They circulated as currency. The artist Malik Gaines (2014) calls cowrie shells the “worthless currency with which many Africans traded other Africans into transatlantic slavery.” All of those uses are referred to in Leigh’s work, sometimes decorative (at the end of a braid) and sometimes descriptive, (an eye, a mouth, a vagina, an anus). Leigh’s figure neither confronts you with her gaze nor averts her eyes from yours. She has no eyes. There is no looking at or looking away.

Figure 4. Side view of Brick House with braid and cowrie shells

Figure 4a. Cowrie Shells

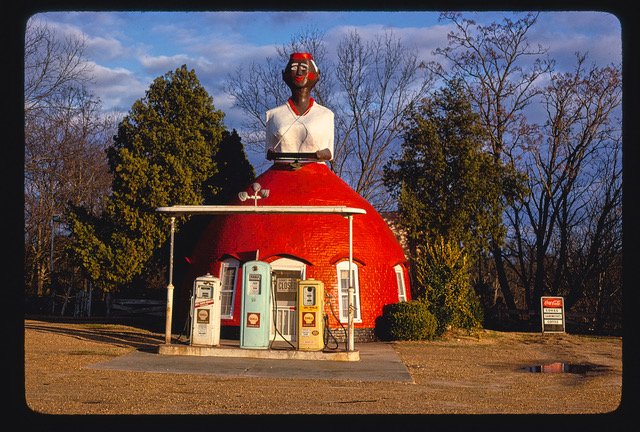

The figure’s long, delicate neck rests upon a dome-shaped torso that resembles both a clay house, (a home in Benin and Togo) and a pancake house outside Natchez, Mississippi called Mammy’s Cupboard. (Figures 5, 6, 7) The latter is a woman who started out black and holding a serving tray, but who isn’t and doesn’t anymore. According to Gaines, Leigh’s reference plays “with ideas of the body as vessel, the body as consumable, the body as service item.” Leigh’s figure may be silent and still, but she is not obsequious. And she is definitely not working. Leigh received the Golden Lion award, for Brick House.

Figure 5. Clay House, Benin

Figure 6. Mammy’s Cupboard Pancake House outside Natchez Mississippi

Figure 7. Mammy’s Cupboard, now white, now without tray

The United States Pavilion which the U.S. State Department awarded to Leigh is called, ‘Sovereignty’. Leigh’s definition of sovereignty is to be “the author of one’s own history”. Not easy for a woman, harder still for a woman of color. With her work, Leigh seeks to transform racist markers into markers of self identity and strength.

Like Brick House, for Sovereignty, Leigh drew upon a wide variety of sources, both historical and contemporary, American, European and African. Leigh’s idea for this installation began 30 years ago, in 1992, when she picked up, completely by chance, a slender volume of souvenir photos from the 1931 Paris International Exposition (Figure 8). At that exposition France and the other colonial powers showed off their colonial holdings.

Figure 8. 1931 Paris International Colonial Exposition

The temporary buildings for the 1931 International Exhibition have all disappeared. One building survives, the Palais de la Porte Dorée (Figure 9) which has had its own troubled past, kicked around like an Art Deco football by one French president after another until it arrived at its present iteration - the Musée de l’Histoire de l’Immigration. I saw an exhibition there on Picasso the Immigrant, harassed and threatened for years by the French authorities because of his anti-Fascist works and words. It was revelatory.

Figure 9. Palais de la Porte Dorée, Musée de l’histoire de l’Immigration & my favorite swimmer

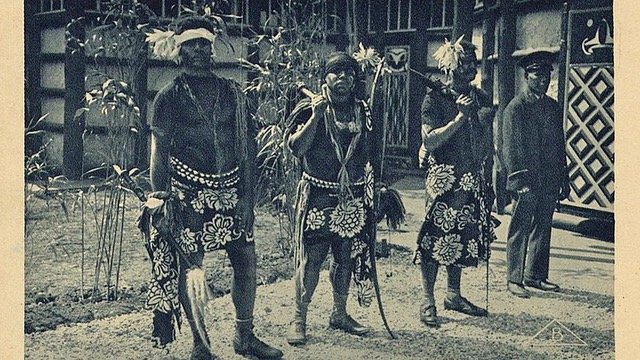

French and other colonial powers celebrated their colonies by building facsimiles of those countries’ buildings. Some participant countries went even further, they brought ‘natives’ to inhabit those buildings. (Figure 10) It wasn’t a new concept, artists like Albert Bierstadt, working in 19th century America, often made money by charging admission for people to see their grand paintings of the American West. To enhance the verisimilitude of their scenes, they presented actual native Americans going about their daily chores, as a tableau vivant. Further back still, in 1550, to welcome Henri II and Catherine de Medici to their city, Rouen recreated a Brazilian village complete with natives. (Figure 11) Rouen was the main French port through which cloth dyes from Brazil were traded. The Rouennais wanted to remind Henri II that this trade was essential to them.

Figure 10. Men from Caledonia

Figure 11. Henri II’s Entry into Rouen, with Brazilian village to the left

After centuries of ‘using’ indigenous people to celebrate their own power, Simone Leigh turned the tables and transformed representation into presentation. For the American Pavilion, she created a “1930s African palace,”starting by giving the American pavilion a new set of clothes. She covered its classical, Palladian facade with thatched raffia. No longer did it recall Thomas Jefferson’s Virginia plantation Monticello built by slave labor. (Figures 12, 12a) Using a photo from that booklet she had found 30 years earlier, Leigh transformed the pavilion into a West African rondavel, (Figure 13) from a structure confirming ownership to one confirming independence. As Siddhartha Mitter (NYT 2022) so perfectly states, “Leigh has mined colonialist histories to turn national pride on its head, or in this Pavilion’s case, to shroud it in thatched raffia.”

Figure 12. Exterior of U.S. Pavilion, Giardino, Venice

Figure 12a. The classical pillars of the US Pavilion hidden by Leigh’s transformation of it.

Figure 13. Rondavel, West Africa

At the center of the courtyard, is a statue called Satellite. (Figure 14) Leigh based its form on the ‘D’mba,' of the Baga people on the Guinea coast. A traditional D’mba is a huge female figure with hanging breasts, a symbol of universal motherhood. (Figures 15, 15a) During ceremonies, the D’mba is carried on the wearer’s shoulders. The wearer is covered with fabric, making the D’mba even larger, even more imposing. Leigh has kept the pendulous breasts but transformed the head into a satellite dish, a reference to the D’mba as a vessel that receives and a tool that communicates.

Figure 14. Satelite, Simone Leigh, US Pavilion, Giardino, Venice

Figure 15. Photograph of D’mba mask being worn

Figure 15a. D’mba mask, Baga people

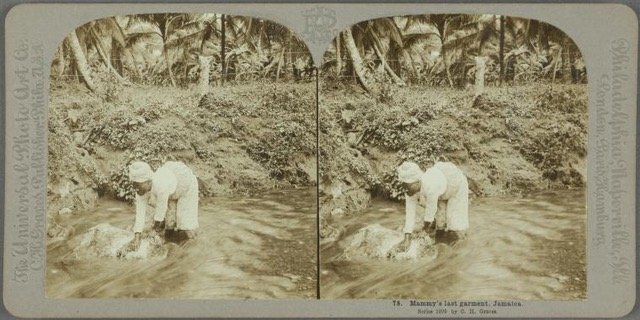

Inside the pavilion, one statue didn’t seem far enough from its source to transform it into an image of empowerment. Called Last Garment, (Figure 16) it is a statue of a woman at the edge of a reflecting pool, bent over, pounding laundry against a stone. Leigh’s statue recalls the backbreaking work of women, especially enslaved black women. Her archival reference was an 1879 photograph taken in Jamaica by C. H. Graves called Mammy’s Last Garment. (Figure 17) Images like this were circulated to promote white tourism in the British-occupied Caribbean colonies.

Figure 16. Last Garment, Simone Leigh, 2022

Figure 17. Mammy’s Last Garment, C.H. Graves, 1879 stereoscopic views

Anonymous, (Figure 18) is another young Black woman with huge undefined hands holding her eyeless face. She’s a reference to another racist image, this time an 1882 photograph by James A. Palmer, (Figure 19) a white photographer in South Carolina who, like his contemporary in Jamaica, made souvenir images of Black people.

Figure 18. Anonymous, Simon Leigh

Figure 19. Photograph of young woman from South Carolina with Edgefield jug

Jug, (Figure 20) with a reflective white veneer covering jagged cowrie shells recalls the jug in the photo of the young woman from South Carolina, which is an example of Edgefield stoneware jugs (Figure 21) made by enslaved peoples in South Carolina updated here with Leigh's signature cowrie shells.

Figure 20. Cowrie Jug, Simone Leigh

Figure 21. Edgefield Stoneware Jugs, made by South Carolina Slaves

Archival images and material culture, mostly from Africa and the American south, are Leigh’s inspiration. Her work explores black female identity and feminism. How she makes these themes her own, makes them important. Her artwork which she describes as auto-ethnographic, is important and beautiful.

Simone Leigh’s work is worth seeking out, if you are in Boston anytime from April through September, I urge you see her work at the ICA, which, with the cooperation of the U.S. State Department, supervised Leigh’s Biennale Pavilion.

Copyright © 2023 Beverly Held, Ph.D. All rights reserved

Dear Reader, I hope you enjoyed reading this article. Please sign up below to receive more articles plus other original content from me, Dr. B. Merci!

And, if you enjoyed reading this review, please consider writing a comment. Thank you.